For 7,000 years, the Mississippi River has snaked across southern Louisiana, depositing sediment from 31 states and 2 Canadian provinces across its delta. As sediment accumulated under water, plant communities began to develop, trapping more sediment and building land.

Delta Lobes

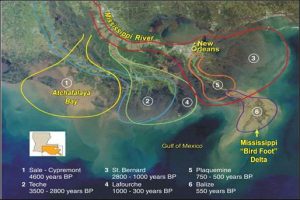

As each section of land—called a “delta lobe”—continued to build, the Mississippi River’s path to the Gulf of Mexico became longer and more difficult. In response, the river would eventually change course, abandoning the older lobe and cutting a shorter route to the Gulf, starting the process again. These abandoned lobes gradually sank and eroded, forming extremely productive estuaries and leaving behind barrier islands to mark their former boundaries. New lobes formed with the river’s new route, building up new land for marsh plants and trees to take hold. This constant ebb and flow created a dynamic and ever-changing mosaic of habitats and natural resources.

As each section of land—called a “delta lobe”—continued to build, the Mississippi River’s path to the Gulf of Mexico became longer and more difficult. In response, the river would eventually change course, abandoning the older lobe and cutting a shorter route to the Gulf, starting the process again. These abandoned lobes gradually sank and eroded, forming extremely productive estuaries and leaving behind barrier islands to mark their former boundaries. New lobes formed with the river’s new route, building up new land for marsh plants and trees to take hold. This constant ebb and flow created a dynamic and ever-changing mosaic of habitats and natural resources.

Natural Levees

The river also created the natural levees on which early communities were built, by depositing sediment during periods of high river flow or spring floods. At times, the river would break through its natural levees, depositing sediment and fresh water in the surrounding wetlands, keeping them healthy, productive and intact. These lush and fertile wetlands protected our communities from storm surge and hurricanes.

Birdsfoot Delta

By the time of European settlement, the Mississippi River Delta plain stretched across a remarkable 7,000 square miles, making it one of the largest river deltas in the world. At this time, the river passed through an area now often called the “Birdsfoot Delta.” Because the end of this lobe lies near the continental shelf and thus deep water, it provided tremendous opportunities for waterborne commerce and transportation, leading to the rise of New Orleans and other port cities and trade routes.

By the time of European settlement, the Mississippi River Delta plain stretched across a remarkable 7,000 square miles, making it one of the largest river deltas in the world. At this time, the river passed through an area now often called the “Birdsfoot Delta.” Because the end of this lobe lies near the continental shelf and thus deep water, it provided tremendous opportunities for waterborne commerce and transportation, leading to the rise of New Orleans and other port cities and trade routes.

A natural delta exists in a state of constant change. Today, the Mississippi River Delta’s natural cycles of change and rebirth have been constricted by human activities such as leveeing of the river for navigation and flood control, laying the groundwork for today’s ecological collapse and land loss.