Every summer, a low-oxygen area, often referred to as a Dead Zone, develops off of the Texas-Louisiana shelf when nutrient-laden fresh water from the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers flows into the Gulf of Mexico. While it seems contradictory, nutrients brought in from the river that fuel the region’s plant, wildlife and fisheries productivity are the same nutrients that contribute to the formation of a low-oxygen area along parts of the Gulf’s seafloor. Mobile fish and marine mammals are able to swim away from the low oxygen area, but weaker swimming organisms can be trapped and die, leaving behind a barren area that would typically be teeming with life.

WHAT CAUSES THE DEAD ZONE?

The Dead Zone develops, somewhat ironically, as a result of the nutrients that fuel the high productivity in the Gulf’s surface waters. As dead plant material falls from the surface through the water column deeper into the Gulf, bacteria consume it using oxygen. This lack of oxygen creates the Dead Zone in bottom waters on the Texas-Louisiana shelf throughout warm summer months. This occurs when there are fewer storms and strong winds to mix the warm, oxygenated surface waters and the cooler, deeper waters. At other times during the year, winds, weather fronts and storms in the area mix the water, replenishing the oxygen used by the bacteria in the deeper water.

WHAT IMPACTS DOES THE DEAD ZONE HAVE?

The size of the Dead Zone generally depends on the quantity of fresh water and nutrients entering the Gulf of Mexico from the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers. This year, the river was in flood stage for more than 240 days at Red River Landing, an unprecedented length of time. Results released from the annual cruise, led by Louisiana State University scientists found the Dead Zone was nearly 7,000 square miles – the 8th largest ever measured. Non-swimming and weak-swimming animals can die if they are trapped in the low-oxygen area. For fish and marine mammals, the Dead Zone can cause them to move away into deep waters.

WHERE DO THE NUTRIENTS COME FROM?

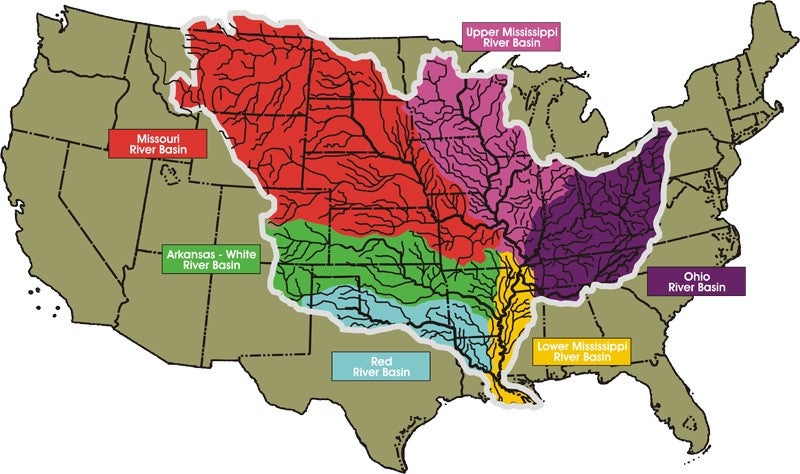

The Mississippi River and its tributaries meander more than 2,000 miles through parts of 32 U.S. states, collecting the sediment, fresh water and nutrients from the one-million-square-mile drainage basin, bringing them south to Louisiana and the Gulf of Mexico. Sediment, fresh water and nutrients can all be good things, but too much of a good thing can have unwanted consequences.

The Mississippi River and its tributaries meander more than 2,000 miles through parts of 32 U.S. states, collecting the sediment, fresh water and nutrients from the one-million-square-mile drainage basin, bringing them south to Louisiana and the Gulf of Mexico. Sediment, fresh water and nutrients can all be good things, but too much of a good thing can have unwanted consequences.

Nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorous, are essential for an abundant food supply, but crops take up on average just 40% of the nitrogen that is applied each season. The excess can run off into waterways, leading to a high nutrient load in the Mississippi River. Many efforts are underway throughout the Corn Belt to improve fertilizer efficiency and increase adoption of practices like cover crops and buffer strips that protect water quality.

HOW CAN LOUISIANA HELP REDUCE THE DEAD ZONE?

Reducing nutrient input is important for reducing the size of the Dead Zone. Louisiana has a nutrient reduction strategy that includes using river diversions. River diversions are restoration projects designed to build and sustain Louisiana’s coastal wetlands. These wetlands can also help filter and remove nutrients from the river, fueling wetland plant growth while also reducing nutrients that cause the Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone.

NOT JUST A LOUISIANA ISSUE

Reducing nutrient input in the Mississippi River itself is critical to reducing the size of the Dead Zone in the Gulf, but Louisiana alone didn’t create the problem and Louisiana alone can’t solve it. While most Restore the Mississippi River Delta efforts focus on coastal restoration here in Louisiana, our individual organizations also work throughout the Mississippi River Basin to improve the management of the Mississippi River system.

We all work to defend the Clean Water Act. The best way to improve water quality is to prevent pollution at its source, which is much cheaper than trying to remove pollution downstream. We are working to protect and defend the Clean Water Act (CWA) against various attacks and attempts to remove clean water safeguards that have protected our nation’s wetlands and streams since the 1970s.

Here are some other examples of some of the work that our national organizations is doing for the health of the entire Mississippi River Basin.

National Wildlife Federation:

The National Wildlife Federation is working to minimize impacts on water quality of the excess fertilizer we send downriver can be mitigated before the water reaches the Gulf. Agricultural practices such as planting cover crops and preventing drainage from farm fields into the river can reduce the load of fertilizer at its source. Broad floodplains filled with wetlands can filter nutrients in the river water before it reaches the Gulf. The river that was cut off from its floodplain by levees for flood control and channels for navigation can be reconnected via controlled diversions of water and sediment.

- WORKING WITH FARMERS: We work with farmers and landowners upriver to promote responsible conservation practices, like planting cover crops and protecting prairie potholes and other marginal farmland important to wildlife, all of which protects acres that help absorb excess fertilizer bound for the Gulf.

- MAINTAINING CONNECTIONS BETWEEN RIVERS AND FLOOD PLAINS: We work to prevent the construction, with tax dollars, of Corps of Engineers water projects that sever yet more of the connections between the river and its floodplain, destroying wetlands that absorb fertilizer and replacing them with farms and developments that increase fertilizer run-ff. One example is a scheme to drain wetlands in the New Madrid Floodway one of the last connections between the river and its floodplain, providing important fish and wildlife habitat and critical flood protection.

Environmental Defense Fund:

The Environmental Defense Fund is working with farmers to adopt practices that reduce fertilizer runoff, including partnering with the National Corn Growers Association to improve environmental outcomes while optimizing productivity and profitability. EDF scientists discovered that – with a combination of efficient fertilizer practices, cover crops and restoring wetlands and other natural infrastructure across the Corn Belt to trap and treat nitrogen lost from farms – we can reach the Environmental Protection Agency’s goal of shrinking the Gulf of Mexico’s dead zone to a safe level.

These findings, along with parallel research highlighting the primary reasons for nitrogen losses in the Corn Belt, are helping inform policy and target agricultural funding where it is needed most. EDF has also:

- Worked with farmers and their advisors to establish farmer networks that conduct real-world testing of fertilizer applications on farms.

- Helped farmers share the results to determine best practices for delivering the highest yield with the greatest conservation benefits.

- Helped reduce fertilizer loss by an average of 25% on 750,000 acres across the U.S. while maintaining or increasing crop yields.

Now, EDF and partners have used this knowledge to create a Farmer Network Manual for agricultural practitioners interested in conducting their own on-farm research.

National Audubon Society:

The National Audubon Society conservation program works through science, education, advocacy and on-the-ground conservation to ensure that birds and people have a healthy environment to live and thrive. Audubon’s water strategy works to enhance water quality and quantity while our coastal strategy promotes restoration of coastal habitat like wetlands, which filter harmful contaminants from water. The combination of both strategies enhances habitat for birds and reverses harmful algal bloom events, while providing healthy drinking water for people.

- From restoring wetlands to advocating for state policies like Ohio’s H2Ohio and federal programs including the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, our Audubon Great Lakes office is ensuring that safe and clean water runs throughout the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico.

- At the federal level, there are various programs that fund hazard mitigation and infrastructure development to protect communities from storms. Audubon’s advocating for changes to allow these programs (such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Pre-Disaster Hazard Mitigation Grant Program) to fund natural infrastructure projects alone or alongside grey infrastructure (sea walls, jetties, etc.) to enhance habitat, increase the lifetime of grey infrastructure, absorb flood water, and filter contaminants from the environment.