The Geology of Land Building Using Mississippi River Sediment Diversions

This is part three of the series “Building Land in Coastal Louisiana: Expert Recommendations for Operating a Successful Sediment Diversion that Balances Ecosystem and Community Needs.” View parts one and two.

Successfully operating a sediment diversion in Louisiana requires that we understand how water and sediment naturally flow in places where the river enters the coast. The basic physical processes are relatively simple. When a sediment-rich river, like the Mississippi, enters an open bay, the flow spreads out and sediments are deposited in the quiet areas, which builds land.

This process is responsible for the growth of nearly 25,000 square miles of new land in the Mississippi River Delta over the last 7,000 years. These dynamics also helped create several hundred square miles of land at the mouth of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers over the past century. Given how effective the river can be at building land, if building land was the only constraint on operating diversions, then diversions would be open for most, if not all, of the year; but this is not feasible due to possible negative effects to fisheries, industry and navigation, among other factors.

Building land quickly is so important that the state of Louisiana is looking at ways to make the process as effective as possible while minimizing negative effects. From the perspective of the receiving basin, this means looking into ways to enhance the sediment trapping efficiencies of diversions.

In our recommendations report, we suggest that the state should trap at least 75 percent of sediments entering coastal bays within the bay itself. This is challenging, and likely involves building artificial barrier islands to break down winds and waves as well as constructing marshes in the flow path of the diversion, to provide places for sediments to settle. Scientists do not yet fully understand the exact size and shape of these systems, but they should likely follow the shape of natural river mouth features and barrier islands in the Mississippi River Delta.

|

|

What can we expect, in terms of land building, from a Mississippi River sediment diversion? Over the long haul, we should see a very substantial amount of land building near the diversion. After a period of several decades, we can expect a fan-shaped system with a main channel extending from the mouth of the diversion, and multiple smaller channels extending in a branching pattern downstream.

The areas along the channel edges will likely be mineral-rich natural ridges, resistant to erosion, and likely lined with willow trees. The edges between the ridges will be lower ponding areas, filled with lotuses, arrowheads and other wetland plants. These areas will not develop overnight; it could take a period of several years for enough sediments to be deposited on bay floors for these bays to accrete to the point where plants can take root and grow.

We should also be clear that land building will not occur everywhere. In places next to the diversion outfall, river currents may be moving so fast that scour and erosion occurs. As such, those managing the diversions may want to open the system slowly, to minimize this erosion. We can also expect the land-building impacts of the diversion to be felt probably 10 to 20 miles from the diversion’s mouth, as coastal currents and winter storms rework sediments and places them on distant marshes.

Overall, we can expect substantial land building from river diversions, but we must be careful in how we operate these systems to reduce scour and enhance sediment trapping.

Stay tuned for the next post in the “Building Land in Coastal Louisiana” series about key recommendations concerning socio-economics, titled “Building Land While Balancing Historic and Cultural Effects.”

For more information about the Sediment Diversion Operations Expert Working Group’s key recommendations, visit http://www.mississippiriverdelta.org/diversion-ops-report/.

Dr. Alex Kolker is currently an Associate Professor at the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium and teaches in the Department of Earth and Environmental Science at Tulane University. He studies the geology and oceanography of coastal systems, with a focus on delta development, climate impacts and groundwater. He is a member of the Sediment Diversion Operations Expert Working Group and co-author of their report, “Building Land in Coastal Louisiana: Expert Recommendations for Operating a Successful Sediment Diversions that Balances Ecosystem and Community Needs.”

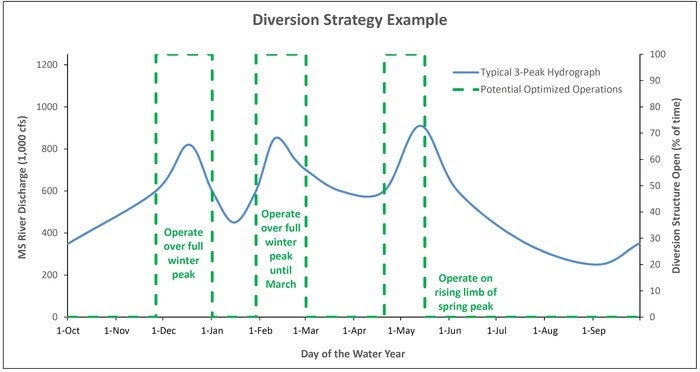

One potential operation strategy focused on effectively using river hydrology and capturing

One potential operation strategy focused on effectively using river hydrology and capturing