What Can the 1927 Flood Teach Us About Coastal Restoration?

During the historic 1927 flood, a portion of the Mississippi River levee south of New Orleans was dynamited to lower the water level and prevent catastrophic flooding – seen in much of the Mississippi River Basin – from occurring in the city. This explosion created a 2-kilometer wide crevasse, which redirected water into nearby Breton Sound.

Nearly 90 years later, scientists have completed measurements in the upper Breton Sound basin to quantify the sediment deposition in the 50-square-mile crevasse splay created by the levee break.

In the study, “Sediment Deposition at the Caernarvon Crevasse during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927: Implications for Coastal Restoration,” John W. Day et al. state that “The 1927 crevasse deposition shows how pulsed flooding can enhance sediment capture efficiency and deposition and serves as an example for large planned diversions for Mississippi delta restoration.”

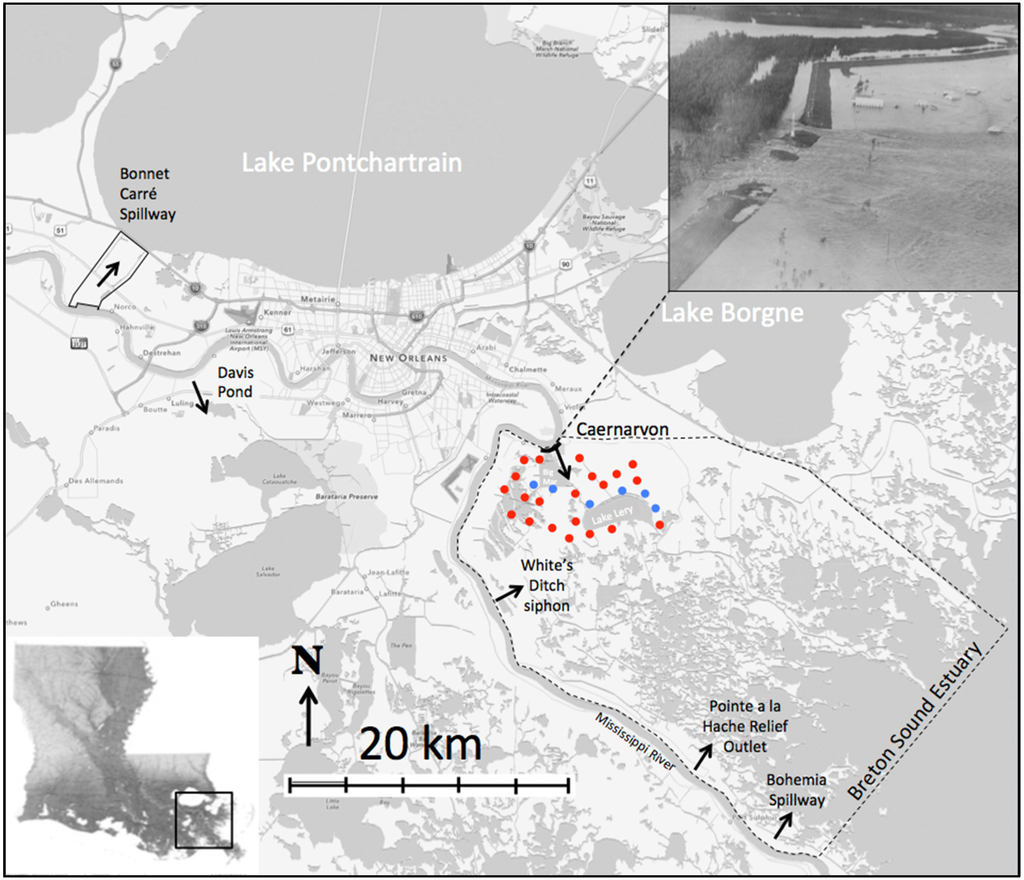

Figure 2. The Breton Sound Estuary. Dots indicate where core samples were taken and the approximate area of the crevasse splay deposit based on researchers’ measurements. Blue dots indicate cores that had additional analysis carried out. Upper right inset: aerial photo showing Mississippi River flowing through the 1927 Caernarvon levee breach. Dark black line at the site of the crevasse is the estimated width of the levee breach. John W. Day et al.

Researchers found a distinct layer of sediment from the 1927 crevasse, ranging from 0.8-16.5 inches thick, at 23 of the sites they sampled, with the thickest layer closest to the river. The investigators estimated that more than 40 million tons of sediment flowed from the Mississippi River into Breton Sound during the 108 days the crevasse was open.

The marshes in the splay captured approximately 55-75 percent of the suspended sediments that poured through the crevasse, which resulted in the deposition of roughly 30 million tons of sediment within the 50-square-mile crevasse splay. In one core, the sediment deposition rate in 1927 was at least 0.8 inches per month – that’s 10 times more than the annual post-1927 average. The results of this study could have important implications for future coastal restoration projects, specifically sediment diversions.

Lessons learned for restoration

The flood of 1927 was an unprecedented, fatal flood that caused massive and widespread economic and structural damages. Louisiana, as well as all the other communities along the Mississippi River, are now largely protected by a federal system of levees and spillways, as evidenced during this year’s winter flood.

But the 1927 flood also provided a major land-building opportunity, as wetlands help provide protection from future flooding and loss of life. Large, episodic flood events, like the 1927 flood and this winter’s high-water event, can be used to build vast land in relatively short periods of time, while balancing the needs of the ecosystem and the people and wildlife that depend on it.

The state of Louisiana is currently working to engineer and design controlled river diversions, which would harness the power of the river to build land. This past fall, the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority voted to advance the Mid-Barataria and Mid-Breton sediment diversions. Controlled sediment diversions like these are vital components of any large-scale restoration plans.

Possible effects on fisheries

Despite their land-building potential, there currently exist some questions and concerns about how sediment diversions will affect fisheries. The researchers determined that the periodic opening of flood control structures, such as the Bonnet Carré Spillway and the 1927 crevasse, during high-water events, demonstrate the balance that can be achieved between inflows of fresh water and fishery concerns.

“The periodic opening of the Bonnet Carré Spillway and the 1927 crevasse at Caernarvon serve as good models for understanding the significance of this fishery concern. The periodic openings have minimized algal blooms to short periods and resulted in larger fisheries catches in years following openings,” the study says.

“Given predictions of accelerated sea level rise, increasing human impacts, and growing energy scarcity, delta restoration should be aggressive and large-scale. We believe that restoration of the Mississippi delta will require diversions similar in scale to historical crevasses if they are to be most effective.”

How was the research conducted?

The scientists collected 23 sediment cores that extended down 1 meter throughout the 50-square-mile crevasse outfall area. The core sediments were analyzed for sediment type, properties and age. Deposition of sediment from the crevasse extended over seven miles from the break in the levee.

The 1927 sediment deposits were found at an average depth of 13.8 inches below the marsh surface, suggesting a post-1927 deposition rate of 0.2 inches per year. Deposition rates ranged from 0.2 to 4.6 inches per month over the 3.6 months that the crevasse was open.

The estimated sediment load entering through the crevasse from the river during the 1927 event was 40 to 54 million tons, and roughly 30 million tons of that sediment was deposited and retained within the 50-square-mile crevasse splay. Based on the varying thickness of the 1927 deposit over the splay, the volume of the 1927 deposit could cover 11.5 square miles with about 3 feet of sediment.

The lessons learned from researching previous high-water events can help planners design the best, most effective restoration solutions to help rebuild wetlands vital to our future.