The History of Coastal Restoration in Louisiana: More than 40 years of planning

By Estelle Robichaux, Restoration Project Analyst, Environmental Defense Fund and Gaby Garcia, Science Intern, Environmental Defense Fund

The damage wrought by Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall in Louisiana’s bird’s foot delta nearly 10 years ago, brought regional and national attention to the state’s dramatic and ongoing coastal land loss crisis. But this crisis, as well as innovative and large-scale solutions to reverse wetland loss, had been studied, discussed and planned by scientists and decision-makers for decades.

In a series of blog posts, we will explore a few of Louisiana’s early restoration plans that, in many ways, laid the groundwork for the 2012 Coastal Master Plan.

More than 40 years of restoration ideas & planning

In 1973, Louisiana State University’s Center for Wetland Resources published a multi-volume report titled “Environmental Atlas and Multi-Use Management Plan for South-Central Louisiana” . The report provides an overview of the Barataria and Terrebonne Basins and recommendations for natural resource management and restoration.

One of the most notable recommendations is initial discussion of a freshwater and land-building river diversion into Barataria Basin at Myrtle Grove, a project now known as the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion. A number of other natural resource management options are described in the plan, including the engineering of barrier islands, use of salt domes for water management, hydrologic restoration and regulation of development.

But not all the ideas have had as much staying power as the notion of harnessing the muddy Mississippi River to restore and maintain coastal wetlands.

Barrier islands in lakes?

Barrier islands are a coastal area’s first line of defense against storm surge, wave action and tides. These islands not only provide important habitat for many bird species, but they protect natural and built infrastructure upon which Louisiana’s economy depends.

This early management plan suggests constructing barrier islands along the shorelines of large lakes and bays, to help stop erosion in these areas. The authors state that these islands would create new, more diversified habitats as well as enhanced recreational opportunities. While these would be nice benefits to have, it would require building a highly engineered, unnatural feature into the landscape.

Not only is this line of thinking something that ecologists and natural resource managers have moved away from, but these projects would not have done anything to address the root causes of land loss. Therefore, they would have been extremely expensive to maintain due to a lack of natural sediment input and continued saltwater intrusion.

Building out of harm’s way

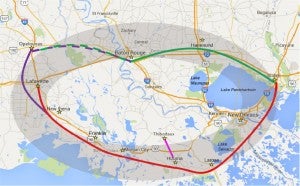

One of the concepts proposed in the report is the establishment of a network of “development corridors” throughout south-central Louisiana. These corridors would ensure limited development in vulnerable coastal areas while encouraging urbanization in areas that have firmer soils, good drainage and are reasonably safe from flooding. They would have been focused on natural levee ridges for land stability and have access to major and minor waterways for commerce.

Interestingly, the areas within the proposed network of corridors are the economic and population centers that many Louisianans are most concerned about protecting today. Moreover, the areas outside of this network, where the authors specifically discourage further development, are those that we now recognize as some of the most vulnerable to increased damage from storms and the threat of sea level rise.

A diversion at Myrtle Grove

Certain solutions in the report still maintain a presence in restoration efforts today, specifically the proposal to construct a freshwater diversion at Myrtle Grove. Today, this project is called the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion and has evolved into a plan to pulse high-velocity river water, full of sediment, into deteriorating wetlands in the adjacent Barataria Basin. Unlike the project defined in the 2012 Coastal Master Plan, the 1973 plan focuses on using fresh water to help establish a proper salinity gradient and combat saltwater intrusion and has other, more complex plans for diverted sediment.

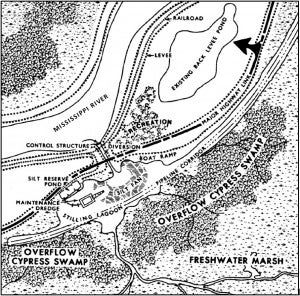

As with today’s sediment diversions, the plan recommends that water flow from the Mississippi River be regulated by a control structure, through a diversion canal and then into the basin. The authors predict that the diverted water would abruptly loose velocity on the basin-side of the canal and deposit sediment in a “silt fan” near the canal mouth. While some sediment would continue out into adjacent wetlands, recreating more naturally occurring conditions, sediment from the stilling lagoon and silt fan would be removed by a small dredge and conveyed via pipeline for either construction or restoration purposes.

As with today’s sediment diversions, the plan recommends that water flow from the Mississippi River be regulated by a control structure, through a diversion canal and then into the basin. The authors predict that the diverted water would abruptly loose velocity on the basin-side of the canal and deposit sediment in a “silt fan” near the canal mouth. While some sediment would continue out into adjacent wetlands, recreating more naturally occurring conditions, sediment from the stilling lagoon and silt fan would be removed by a small dredge and conveyed via pipeline for either construction or restoration purposes.

Evolution in natural resource management & restoration

Clearly, the idea behind what is now a crucial component to Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan, diverting fresh water and sediment from the river to build new land, has come a long way from its humble beginnings. And although many of the proposed restoration and management solutions in the 1973 report did not make the cut, the problems they sought to address still threaten the livelihoods and communities of coastal Louisiana.

Check back as we continue to trace this history of restoration planning in Louisiana, which only emphasizes the great need for restoration action now!

Want to get involved? Take the PLEDGE now to vote in the upcoming elections and urge candidates to support the following restoration principles:

1. Be a voice for coastal restoration progress

2. Protect Existing and Secure Future Coastal Restoration Funding

3. Support the Coastal Master Plan