An Ever-changing River: Examining Where Land Meets Water

Based in New Orleans, Virginia Hanusik is a visual artist whose projects explore the relationship between landscape, culture and the built environment. Through her photography, she manages to beautifully capture the visual narrative of climate change on the Mississippi River and the surrounding areas. Her work has been featured internationally across major publications like The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and National Geographic, to name a few.

Her dedication to telling the story of the delta continued last year in her role as a Rising: Climate in Crisis Resident at Tulane University’s “A Studio in the Woods,” where she depicted the inequality of disaster relief along the Gulf Coast.

Recently, I caught up with Virginia to learn more about her interest in the Mississippi River Delta and how she uses her artistry to capture its story in her work.

Virginia, your photos of Louisiana’s architecture and landscape are a unique approach to documenting the impacts of the climate crisis. Tell us about your process.

My background in architecture has heavily influenced my practice and how I understand larger societal systems to be physically manifested in the world. Most of my projects begin with questions about how and why we inhabit the spaces we do and the valuation of the land itself.

Much of your work shows the growing threat climate change and coastal erosion poses for homes and communities near waterways. What is it like to photograph these spaces and see our impact on the land firsthand?

I’ve always been drawn to the liminality of the coast and our attempts to make things permanent in a landscape that is meant to shift and transform. Photographing the architecture and infrastructure of these areas, where land meets water, is a way of examining the engineering of the natural environment and the concepts, behaviors and policies that have contributed to the climate crisis.

You have been photographing Louisiana’s landscape and infrastructure since 2014. How has the landscape changed since you first began this project?

The changes I’ve observed in my short time working here are minor compared to the transformation witnessed by folks who have lived on and experienced this land for generations. However, while taking photographs, I’ve seen explicit changes in structure (newly raised houses) and geography (the shrinking size of a barrier island).

Your work spans across South Louisiana and highlights the unequal flood risk experienced by different communities. How do these landscapes differ?

Infrastructure is not neutral, and exploring the impacts and limits of our flood protection system is a central part of my work. I think—especially in the past several years—it’s become more evident that no engineering solution will completely absolve us from the compounding environmental and social challenges we are facing. For example, we’ve not only encouraged but incentivized the development of high-risk flood zones. We are experiencing the impacts of that at various rates, often along racial and socio-economic lines.

Many of your photos are taken from the river itself. How does it feel to travel through these unique waterways?

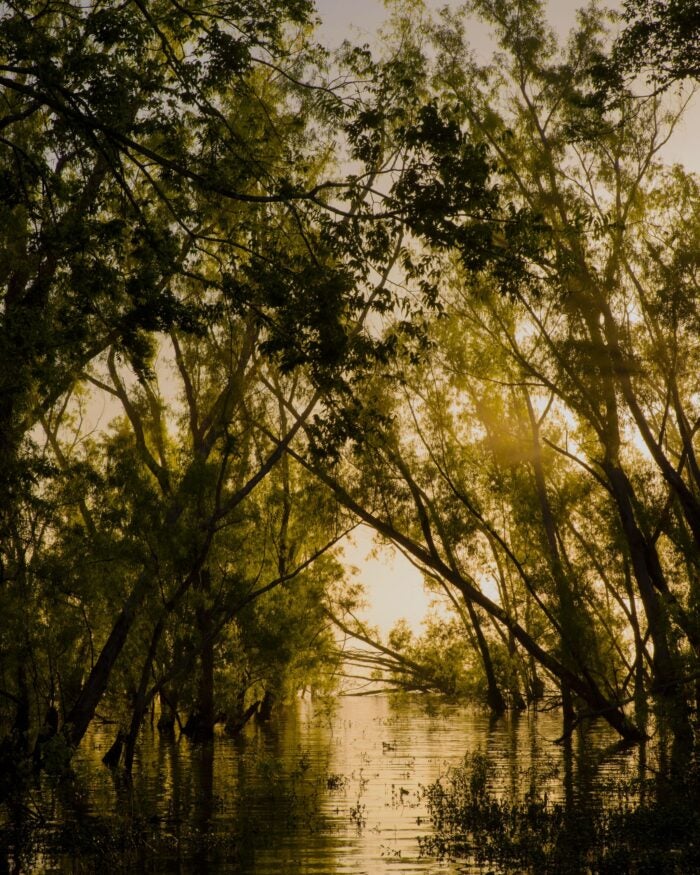

I’m grateful for every opportunity I get to be on the river, which is sometimes on a boat with my friend Richie Blink, who owns Delta Discovery Tours. It’s amazing to see some of the restoration projects underway and witness the difference in vegetation each time I go. The river is such a special, spiritual place that really makes me feel connected to its larger watershed ecosystem when I’m traveling on it.

How do you capture “invisible infrastructure” in your photos?

The environmental parameters we are forced to reckon with today emphasize how living along the water will look very different in the coming decades, especially as invisible infrastructures like flood insurance continue to alter the physical landscape. By focusing on the architecture, landscape, and infrastructure of South Louisiana, my images seek to make visible how we’ve altered the land through temporary technical measures and the unequal distribution of protection.

What’s next for you, and where can people access your incredible work?

I’m working on a book about the visual narrative of climate change and the impact of disaster-oriented imagery. It will be a collection of photographs made over the past eight years in Louisiana paired with a collection of essays from contributors that I’m really excited about. I’m also continuing to develop a project about the inequality of disaster relief along the Gulf Coast and recently received funding to continue my research in Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes. My website is a constant work in progress, as is my Instagram, where I post most of my work.