How Social Science can Inform Engineers Working on Coastal Restoration

Growing up in Minnesota, I loved swimming and kayaking along the Mississippi River. This summer, as part of my EDF internship I learned about life 2,000 miles downriver in Louisiana. To both Minnesota and Louisiana, the Mississippi River is culturally and economically important, but also poses risks that will worsen as climate change progresses. In high school, I remember stuffing and laying sandbags to protect my teacher’s home from flooding ahead of a storm. And storms like those are expected to intensify in Minnesota.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Experiences and knowledge like this motivated me to major in civil and environmental engineering at the University of Virginia (UVA). I learned that engineering is a way of thinking and problem-solving, and I developed a set of tools to break down and tackle new challenges. Most of these tools consist of math and science fundamentals – but social science is a powerful, underutilized tool for engineers working in climate resilience.

Social science can help engineers define complex socio-ecological systems, understand stakeholder beliefs and values, and create more inclusive design processes. With a changing climate, collaboration between engineers and social scientists is increasingly important. Engineers do not need to become social scientists, but instead should be open to partnerships, tune into the latest studies and explore the intersections between engineering and social science.

Here are three ways engineers can leverage social science in coastal planning and engineering.

1. Social Science can demystify complex socio-ecological systems.

Engineers play a central role in building resilience. We design infrastructure, model sea level rise and communicate fundamentals of the physical world. But engineering alone is not enough to understand the complex interactions between humans and the environment, referred to as socio-ecological systems.

As described in a recent six-year social science study in the Nothern Gulf of Mexico, which interviewed natural resource managers, educators and community stakeholders in Mississippi, Alabama and Florida, “development planning decisions will affect natural areas [and] vice-versa.”

One connection identified in the research was the potential conflict as both humans and coastal marshes move inland in response to sea level rise. Coastal marshes destroyed by sea level rise may have nowhere to transition due to conflict with human developments. Scientists in this field fear planners and citizens will not recognize the economic value and protection natural infrastructure provides.

Knowledge of socio-ecological systems gives engineers insight on how the environment benefits a community’s well-being and can guide engineers as they determine how to shift infrastructure and how to balance implementing hard (e.g., bulkheads, levees) and natural (e.g., coastal marshes, living shorelines) infrastructure in response to sea level rise.

2. Social Science can help identify factors that drive decision making.

Factors that drive decisions include values, beliefs, perceived risk and vulnerability. Understanding what motivates people to participate in or support mitigative and adaptive actions is important for engineers and resilience planners. EDF has recently undertaken two studies to examine stakeholder beliefs and values in relation to coastal risk, restoration and mitigation strategies in Louisiana. Although these projects are ongoing, there are similar studies that have examined these themes.

A woman piles sandbags in front of her hardware store in Brunswick, GA during Hurricane Matthew. Photo Credit: David Goldman/AP

A March 2020 study explored residents’ reasoning for living in coastal Georgia, their future expectations and their intentions to stay in place or move away from the coast. This study was conducted soon after Hurricane Matthew (2016) and Hurricane Irma (2017) damaged the coast of Georgia. It found that those with lower income, younger people and ethnic minorities were more motivated to move away from the coast but lacked the resources to do so.

The study also found that intentions to move actually decreased after Hurricane Matthew and Irma. Participants cited family ties, their peaceful lifestyle and jobs as reasons for staying in place. They also noted they “fared well” during the hurricanes, which may indicate a false sense of security. The study concluded that coastal planners may need to focus on education strategies to emphasize the individuality of storms and help residents understand that faring well in one or two storms does not guarantee future success.

Coastal planners and engineers can benefit from these insights. Understanding how residents view mitigation tactics and coastal resilience, as well as what drives these viewpoints can help inform investments and the allocation of resources.

3. Social science can help improve participation and community engagement.

Solutions that work technologically are not guaranteed to have a community’s support or fulfill a community’s needs. To develop comprehensive and inclusive plans, community members must have authority and influence during the planning and decision-making processes.

This has been demonstrated by the LA SAFE project, which prioritized citizen involvement and resulted in six parish-level adaptation plans. Social science can help engineers facilitate a more inclusive and equitable planning process.

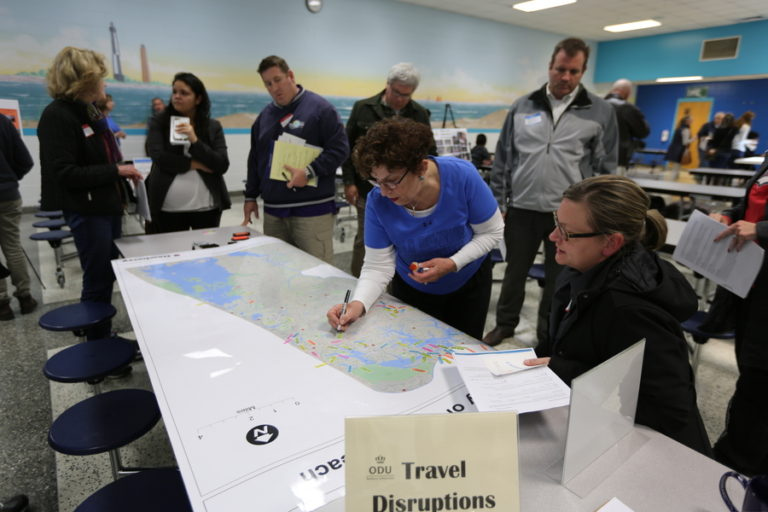

Virginia Beach recently released a coastal resilience plan, created over five years and led by a Seal Level Rise (SLR) committee with numerous engineers from the Virginia Beach Public Works Department and consulting firm Dewberry. In addition to scientific and economic analysis, the committee also accounted for community input and partnered with Old Dominion University (ODU) to promote citizen participation.

Photo credit: Chesapeake Research Consortium

Using the ASERT (Action-Oriented Stakeholder Engagement for a Resilient Tomorrow) framework, researchers at ODU conducted focus groups that included two-way dialogue, acknowledged local concerns and resistance and generated high-quality information from the community. The focus groups also educated citizens about adaptation strategies and ways for them to get involved at different levels.

During the first round of focus groups, the ODU researchers also assessed the effectiveness of the ASERT framework, which participants felt to be inclusive and efficient while producing action and valuable information. With these results in mind, leaders used the ASERT framework in subsequent community engagement meetings over the next three years of the planning process and helped collect input from over 500 Virginia Beach residents. Engineers and social scientists should continue to work together to ensure and expand community engagement throughout the plan’s implementation.

When facing challenges such as climate change and sea level rise, engineers need a plethora of tools. Social science provides invaluable insights about socio-ecological systems, reasoning behind decision-making and can create a more inclusive design process. Engineers should investigate how social science can strengthen their work to prepare communities for coastal hazards and build resilience.