Restore or Retreat? A Difficult Question Facing Many Across Louisiana’s Coast.

In May 2000, our founding fathers (and mothers) brought landowners, port commissioners, parish leaders, restoration advocates, levee experts, business owners and residents together for one purpose—to save our irreplaceable region. They were in the beginning stages of answering the question: Will restoration of Louisiana’s coast require coastal residents to leave their communities? That’s how the name “Restore or Retreat” came about. It was intended as a threat—take action or be forced to leave. Fast forward 17 years, through several devastating hurricanes and the worst oil spill in US history, a report, “Answering 10 Fundamental Questions About The Mississippi River Delta,” by Restore the Mississippi River Delta posed the same question. And now, as the state advances its 2017 Coastal Master Plan and a new program emerges to develop strategies for making coastal communities more resilient, we take another shot at answering this challenging question.

As stated in the original 2012 report, coastal restoration in Louisiana is widely supported. In a recent poll of Louisianans, 95% of those asked say coastal wetlands are either “very important” or “somewhat important.” Residents of Louisiana’s coastal parishes continue to be heavily invested in and have great attachments to their communities. Many coastal communities remain centered around the resources—oysters, crabs and shrimp, as well as oil and gas— and the traditional ecological knowledge and workforce skills that are the backbone of these nationally-significant industries. Finally, social networks in coastal Louisiana are fundamental not only to people’s ways of life, but to their very survival. One has to look no further than the Northshore to see how many St. Bernard residents moved en masse after Katrina to maintain some semblance of their prior social networks and communities.

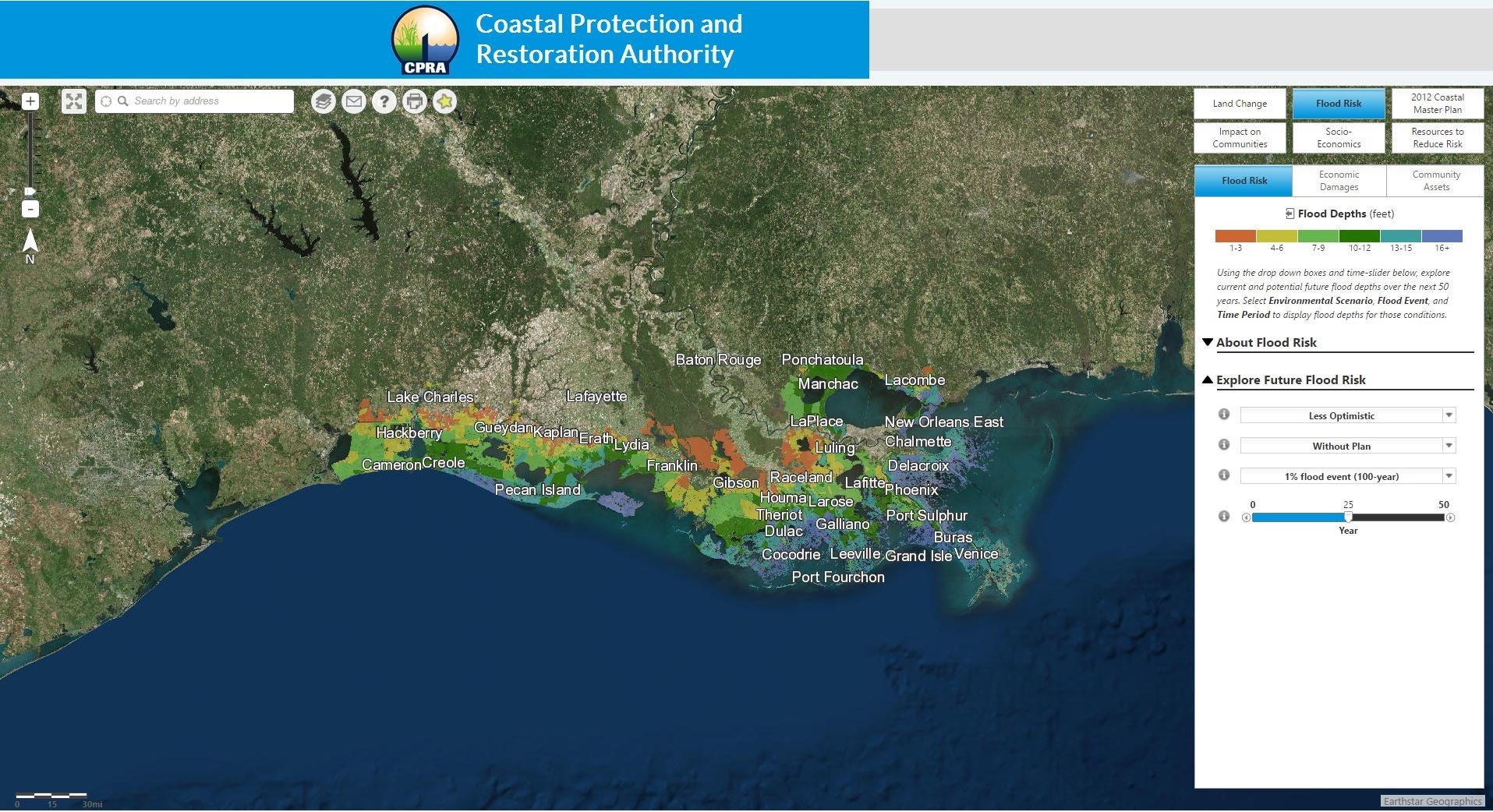

Other areas of the report have evolved, including the statement, “With some exceptions, coastal restoration efforts will not force people from their communities.” The State’s 2017 Comprehensive Coastal Master Plan has worsening environmental conditions that strike deep at the heart of several coastal communities, even those that lie within hurricane protection. Residents of coastal parishes remain deeply invested in their communities, but they also face a “new” reality: The “worst” case environmental scenario from the last master plan update is now the “best” case, according to the 2017 plan. The CPRA Flood Risk and Resilience Viewer allows residents to view flood risk as well as land change in their area using the new “worst case scenario” both with and without the projects in the draft 2017 plan. For most, the science is simply catching up to what they have seen on the ground every day. This makes acting with urgency to implement restoration, protection, and non-structural projects within Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan even more significant.

National interest in these challenges has also piqued through the buzzword of “resilience.” This spring, on the heels of the major progress developing the framework for the State’s Flood Risk and Resiliency program, Louisiana Office of Community Development and philanthropy partner Foundation for Louisiana, will roll out their Louisiana’s Strategic Adaptations for Future Environments—LA SAFE—program for six coastal parishes. LA SAFE and the unprecedented planning associated with the relocation of Isle de Jean Charles were funded with a $92,000,000 grant from the Housing and Urban Development agency and their philanthropy partner the Rockefeller Foundation. This is separate from New Orleans’ own $141,000,000 grant for resiliency.

Over time, our name, “Restore or Retreat,” has slowly become more and more of a realty. Storms did bring about bigger migrations, but still not the wholesale retreat of entire communities. Grandparents moving closer to their children in the big city of Thibodaux. A baby boomer couple selling their home down the bayou to a young, wealthy couple seeking a weekend getaway. Third generation shrimpers opting to go to community college instead of working on the boat for another season. These are the people who have the resources to leave. Others remain tied to their community and investments, like their oyster lugger “parked” in their front yard (i.e. bayou.)

Just as stated in the original 10 Questions report, slowly coastal Louisiana communities are adapting to changing conditions and making difficult decisions about their lives and livelihoods. Today, in 2017, we are better armed with the data and information to help assist in making those decisions of if, how, and when to leave, and where to go.

This is part 6 of our ongoing series where our experts will answer 10 fundamental questions with new and updated information, so that reasonable and scientifically-sound decisions can be made about the long-term sustainability of the delta and surrounding ecosystems. View an introduction to this series as well as posts on sediment, vegetation, diversions, and levees.