Using adaptive management to help restore coastal Louisiana

By Estelle Robichaux, Restoration Project Analyst, Environmental Defense Fund

This post is part of a series about oil spill early coastal restoration funding and projects, be sure to check out parts one and two.

In November 2014, the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) announced that its Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund would award more than $13.2 million to Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) to fund and further develop parts of its Adaptive Management Program. Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan has been designed around an adaptive management approach to ecosystem restoration. The parts of the adaptive management program funded through NFWF will help CPRA make decisions about current and future barrier island and river diversion projects.

What is adaptive management and why is it important?

Adaptive management is a foundational concept in modern ecosystem management and restoration. The primary motivation behind adaptive management is to reduce the uncertainty surrounding actions that will affect an ecosystem or natural resource.

Using a combination of active and passive learning – experimentation and monitoring, respectively – adaptive management answers questions and provides information about how ecosystems react to management actions, such as restoration projects, as part of a science-based decision-making process.

Monitoring is one of the most important components of effective ecosystem restoration and management, though its necessity and usefulness are often misunderstood or overlooked. Monitoring is essential because it helps keep managers informed about short- and long-term trends in an ecosystem.

Long-term monitoring is particularly important because ecosystems are complex, sensitive and often slow to change. For projects, monitoring is essential for proving success or identifying possible areas for improvement or changes in operations.

While project-level monitoring is helpful in learning about localized outcomes of restoration, the BP oil spill highlighted the lack of coordinated, comprehensive monitoring throughout the Gulf region. There are multiple ongoing monitoring efforts in Louisiana, some of which are both long-term and large-scale. However, without coordination among systems, the information produced through monitoring cannot be used to its highest potential in adaptive management, which is an integral part of large-scale ecosystem restoration.

CPRA’s Adaptive Management Program

CPRA’s Adaptive Management Program is made up of more than 20 different components, four of which will be supported by NFWF funds over the next three years.

Coast-wide Reference Monitoring System

Louisiana, in conjunction with the U.S. Geological Survey and funding from the Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act (CWPPRA), has had the Coast-wide Reference Monitoring System (CRMS-Wetlands) in operation for more than a decade. Although the large-scale and long-term information produced by this monitoring system has been very useful, it is not fully comprehensive because it is limited to wetlands.

Barrier Island Comprehensive Monitoring Program

The Barrier Island Comprehensive Monitoring (BICM) program, which was implemented in 2006, was designed to complement CRMS-Wetlands. BICM provides long-term data on Louisiana’s barrier islands to help inform the planning, design, evaluation and maintenance of barrier island restoration projects.

System-Wide Assessment and Monitoring Program

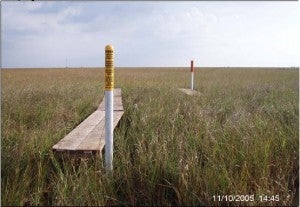

CRMS monitoring station in salt marsh near Caminada Bay. Monitoring gauges are contained in the pipes. Photo: CRMS

The concept of a System-Wide Assessment and Monitoring Program (SWAMP) for coastal Louisiana has been envisioned since the development of CRMS-Wetlands and was proposed under the Louisiana Coastal Area Ecosystem Restoration Study. Although CRMS-Wetlands and BICM are seen as building blocks for SWAMP, these programs do not monitor many important elements of the ecosystem, including coastal waters, non-tidal freshwater habitats, riverine conditions or natural resources, such as fisheries.

CPRA and The Water Institute of the Gulf recently presented on the latest SWAMP components developed, including programmatic monitoring plans at the coast-wide and basin-wide scales and a basin-specific monitoring plan for the Barataria region. The Barataria monitoring plan is nested within the coast-wide framework and its application will serve as the pilot for basin- and coast-wide implementation of SWAMP.

Small-scale Physical Model

Once built,the expanded small-scale physical model the will be one of the largest moving bed models in the world. Representing the lower Mississippi River from Donaldsonville to the Gulf of Mexico in 90 feet by 120 feet, the expanded model will be four times larger in both scale and size than the existing physical model.

Because it is difficult to experiment at the large scale needed for coastal restoration in Louisiana, this model will serve as a proxy for the active learning, or experimentation, component of adaptive management. The expanded small-scale physical model, which is being designed to very accurately represent properties of the river, will help simulate water, sediment and physical dynamics that may result from restoration and management actions. This will help restoration planners make informed decisions about the most effective ways to restore and sustain Louisiana’s coast.

Adaptive management is important to restoration efforts in the Mississippi River Delta because it is a large, dynamic ecosystem and the long-term impacts of restoration may not be observable right away. Managers must stay informed by monitoring the ecosystem and use that knowledge to inform future restoration actions or decisions, so we can have more efficient and beneficial restoration outcomes.

For more information, read part one and two of this blog series.