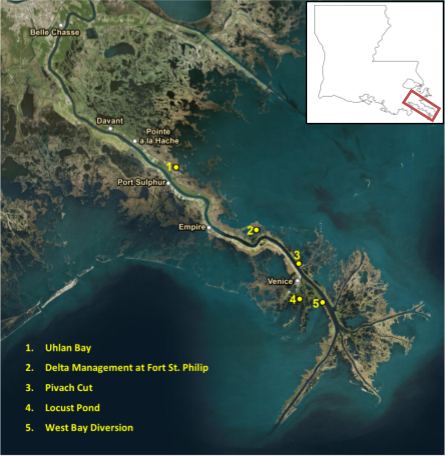

5 Places in Plaquemines Parish Building Land Because of the Mississippi River

A river runs through Plaquemines Parish, but it’s not just any river. It’s one of the largest in the world – the Mighty Mississippi.

The river and its distributaries built Plaquemines Parish over the last 1,000 years, depositing sediment and building thousands of acres of highly productive wetlands. Levees, built along the river for navigation and flood protection, have helped communities in the parish to flourish but have also nearly completely cut off the river from the delta it once built.

According to a recent New York Times article: “The United States Geological Survey calculates that 462 square miles of Plaquemines disappeared into the Gulf between 1932 and 2008. The state’s coastal planners project that 55 percent of what’s left — another 300 square miles — will disappear within 50 years without significant action.”

We often hear that a football field of land vanishes into open water every 100 minutes, and while that’s true for most places along the coast, there are some areas that are exceptions.

Despite levees lining the river on the west bank nearly down to Venice and on the east bank down south of Pointe-a-la-Hache, the river is building land. Here are five places gaining land in Plaquemines Parish because of input from the Mighty Mississippi.

Uhlan Bay

Located east of the Bohemia Spillway, Uhlan Bay receives a steady flow of sediment from the river through Mardi Gras Pass, which has connected the river to the back levee canal since 2012. Since then, sediment has been depositing in Uhlan Bay, causing the bay to shallow and land to begin to emerge from the water.

Delta Management at Fort St. Philip

The Delta Management at Fort St. Philip project (BS-11), constructed in 2006 through the Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act, opened up six crevasses to increase the flow of sediment-laden river water into shallow open water areas and constructed earthen terraces to slow the flow of water to trap river sediment and stimulate land building. Over time, the river has moved through the crevasses, depositing sediment and building land while the terraces have trapped sediment in the Bay Denesse area.

The Delta Management at Fort St. Philip project (BS-11), constructed in 2006 through the Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act, opened up six crevasses to increase the flow of sediment-laden river water into shallow open water areas and constructed earthen terraces to slow the flow of water to trap river sediment and stimulate land building. Over time, the river has moved through the crevasses, depositing sediment and building land while the terraces have trapped sediment in the Bay Denesse area.

Pivach Cut

In 2004, a channel was dredged from the Mississippi River into a nearby shallow open water area, upriver from Baptiste Collette Bayou, to mitigate impacts to wetlands from nearby waterfront development. Over time, the steady flow of the river has deposited sediment in this area, building land.

Locust Pond/Tiger Pass Crevasse

In 1998, the Locust Pond Crevasse was just a small opening from Tiger Pass, a distributary of the Mississippi River, into Locust Pond. The crevasse opening expanded over time, increasing the flow and deposition of sediment into the area, filling in the once open water area just south of Venice with new land.

West Bay Diversion

The West Bay Diversion is a Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act Project (MR-03) that was constructed in 2003 when a cut was dredged from theMississippi River into the shallow, open water of West Bay. In 2009, material dredged from nearby Pilottown Anchorage was used to make sediment enhancement retention devices (SREDs). Following the high river event in 2011, new land began to emerge in West Bay. Additional SREDs have been built in the outfall area using dredged material, and land has continued to build.

These are just a few of the places that are actively building land in Plaquemines Parish. These areas demonstrate the opportunity that exists to use sediment diversions to harness the Mississippi River, and its nearly 100 million tons of sediment that flow through the parish each year, to build and maintain wetlands.

To learn more about how the river can help build and maintain coastal land in the face of ongoing land loss, hurricanes and sea level rise, read “The Mississippi River is Our Greatest Force for Building Land.”