Getting Down to the Basics of Sea Level Rise: Part II

In the news and in studies, we hear a lot about sea level rise, mainly in the form of estimated numbers of future sea level rise and other predictions of how it will affect coastal communities, like in Louisiana. To cut through some of this noise, we thought it would be helpful to break down the basics of sea level rise and discuss what this means specifically here in Louisiana. In a previous post, we explain historical sea level rise that has occurred over time. In this follow-up post, we look at future predictions and how coastal restoration can help ameliorate the effects of increased sea level rise and coastal land loss.

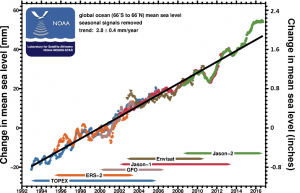

Satellite altimetry data from multiple missions with the seasonal signal removed (Source)

The Rate of Sea Level Rise is Accelerating

Between 1901 and 2010, the average rate of global sea level rise was 0.07 inches per year. From 1992 to 2016, the average rate increased to 0.11 inches per year, meaning global sea levels increased by more than two and a half inches over 24 years.[1] The recent increase in the rate of sea level rise is primarily linked to:

- The

expansion of ocean water due to warming temperatures that cause the same amount of water to take up more space in the ocean basins, resulting in sea level rise;

expansion of ocean water due to warming temperatures that cause the same amount of water to take up more space in the ocean basins, resulting in sea level rise; - Melting of land ice, including glaciers and ice sheets that increase the amount of water in the ocean basins, causing sea levels to rise.[2]

Worldwide sea level will continue to rise during the 21st century.[3] The question is by how much and how fast.

Projecting Global Sea Level Rise

Projecting Global Sea Level Rise

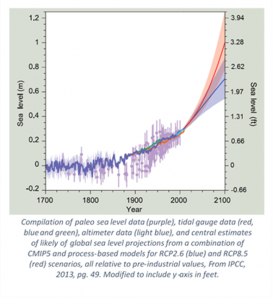

Projecting future sea level rise is not a simple task. To estimate it, scientists use a variety of models and assumptions. Some of these models are based on the physical processes that underlie sea level change, such as heat exchange between the atmosphere and oceans, sea ice dynamics and movement of water in the oceans.[2]

Other models project future sea level rise based on observed statistical relationships between global mean temperatures and observed global sea level.[4,5] New sea level rise projections emerge based on the latest observations and a refined understanding of the processes that drive sea level rise.

As the modeling approach and assumptions differ, so do the resulting global sea level rise projections. Generally, projections of global sea level rise by the year 2100 range from 1.6 to 6.6 feet.[2,6,7] This wide range of projected sea level is a result of the unknowns regarding how large ice sheets, such as the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets, will respond to warming temperatures.[2,7] Even the lower projections of sea level rise could be devastating for low-lying areas like coastal Louisiana if no action is taken.[2]

Planning for the Future in the Face of Rising Sea Levels

Rising sea levels imperil coastal areas around the world. The threat of rising seas, combined with the region’s high rates of subsidence, make relative sea level rise in coastal Louisiana even higher. Around the world, rising sea levels push coastal communities to make hard choices: take action to help shape the future or be passive and let the future and its changes shape you.

In Louisiana, coastal restoration and protection projects are being planned, constructed and maintained in order to actively shape our future for the better. It will be a challenge, but we have an advantage over other coastal areas in the world: We have the Mississippi River. The river, with the sediment and fresh water it brings, built our coastline. Putting the river back to work, where we can – through key restoration projects, including sediment diversions – is the key to helping push back against the threat of rising seas.

[1] NOAA/NESDIS/STAR Laboratory for Satellite Altimetry, accessed 1 November 2015 http://www.star.nesdis.noaa.gov/sod/lsa/SeaLevelRise/LSA_SLR_timeseries_global.php.

[2] Church, J.A., P.U. Clark, A. Cazenave, J.M. Gregory, S. Jevrejeva, A. Levermann, M.A. Merrifield, G.A. Milne, R.S. Nerem, P.D. Nunn, A.J. Payne, W.T. Pfeffer, D. Stammer and A.S. Unnikrishnan, 2013: Sea Level Change. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

[3] IPCC, 2013: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

[4] Rahmstorf, S. 2007. A semi-empirical approach to projecting future sea level rise. Science, 315, 368-370.

[5] Vermeer, M.S. and S. Rahmstorm. 2009. Global sea level linked to global temperatures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 106, 21527-21532.

[6] Parris, A., P. Bromirski, V. Burkett, D. Cayan, M. Culver, J. Hall, R. Horton, K. Knuuti, R. Moss, J. Obeysekera, A. Sallenger, and J. Weiss. 2012. Global Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the US National Climate Assessment. NOAA Tech Memo OAR CPO-1. 37 pp.

[7] DeMarco, K.E., J.J. Mouton and J.W. Pahl. 2012. Guidance for Anticipating Sea-Level Rise Impacts on Louisiana Coastal Resources during Project Planning and Design: Technical Report, Version 1.4. State of Louisiana, Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. 121 pages.