Deltas Around the World are Facing Uncertain Futures – Using the River Can Help

Deltaic systems around the world, such as Louisiana’s Mississippi River Delta and France’s Rhône River Delta, are facing growing consequences from climate change and sea level rise. Sea levels are projected to rise a staggering 1 to 2 cm per year by the end of this century, and deltas around the world will not be able to survive if no action is taken to protect them.

In a recent paper published in Science of the Total Environment, researchers analyzed the impact of flooding events in the early 1990s on sediment deposition in the Rhône delta and what this means for future delta management. Lessons learned there can be applied to other regions facing similar land loss problems, like the Mississippi River Delta in coastal Louisiana.

France’s Rhone River

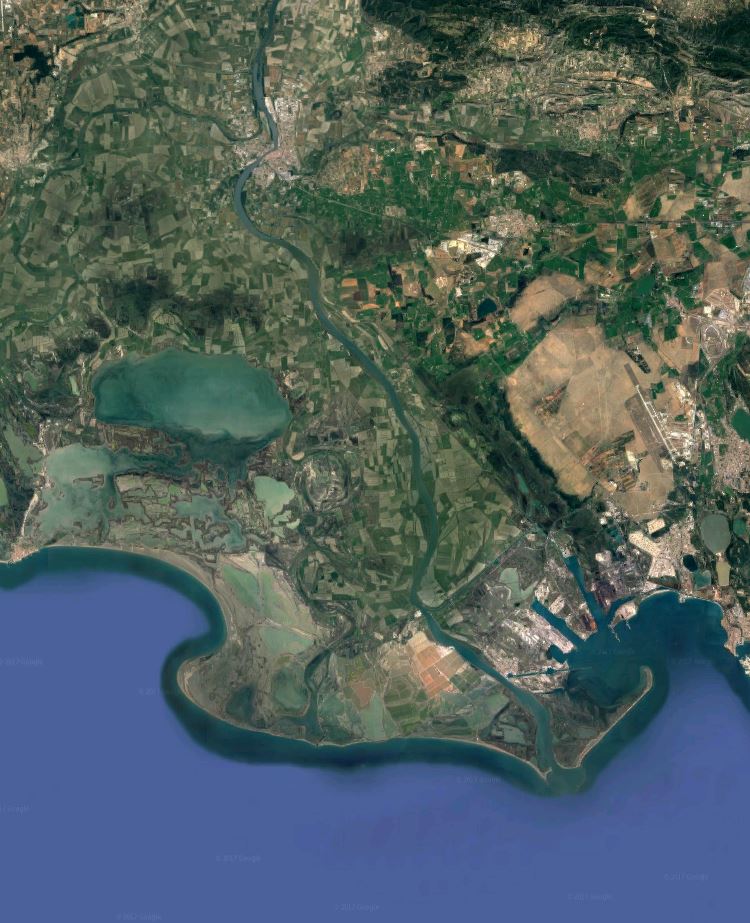

France’s Rhône River delta

The Rhône River meanders through the south of France, eventually draining through its delta into the Mediterranean Sea. Similar to the Mississippi River Delta, human influence, such as channelization of the river for navigation, has significantly impacted the Rhône and its delta.

Regions that are no longer directly connected to a river become sediment-starved, resulting in land loss and decrease in overall productivity. Conversely, wetlands with a direct connection to the river show increased vegetation and sustainability against strong storm events.

Only a small area near the mouth of the Rhône River, La Palissade, remains connected, via a canal, to the main stem of the river and reflects the benefits of regular riverine input, with vertical accretion 10 times higher than other regions as well as an increase in net primary productivity (algae and molecular organisms needed for a healthy ecosystem).

Based on these trends, researchers looked at two specific flooding periods in the early 1990s, to help planners design an effective, sustainable management strategy in the face of climate change.

Rhone delta sediment. Credit: NASA MODIS Dec. 2003

Managing flood events for land building

Flooding periods within river systems provide ample opportunity to use suspended sediments to build wetlands, as typically the highest concentration of sediment occurs during the peak of a flooding event. Not only does flooding offer a chance to capture sediment, it also reduces the salinity in the basin, thereby enhancing wetland productivity.

In coastal Louisiana, the sediment-starved Terrebonne Bay is completely disconnected from the Mississippi River’s influence. Alternately, the Atchafalaya and Wax Lake regions have an influx of fresh water from the Atchafalaya River and therefore some of the lowest land loss rates in south Louisiana, with about 260 km² of new land formed since 1973.

Though the Mississippi River has a significantly higher average annual discharge than the Rhône, the timing of increased sediment is similar, with both rivers experiencing high concentrations of sediment during flood peaks. Measurements like accumulation of sediment and concentration are becoming increasingly important for strategic land building, considering projected sea level rise. With all of this in mind, it becomes apparent that reconnecting the river to its adjacent wetlands and delta is necessary for a sustainable environment.

Sediment diversions: a key restoration tool

Rhone River Delta. Credit: Google Maps 2017

A critical strategy for building land and combatting seal level rise in both the Rhône and Mississippi River deltas is adaptively managing floods to capture fresh water, nutrients and sediment via large gated structures in the levee system – sediment diversions – that would redirect the flow into sediment-starved areas.

In Louisiana, the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion will reintroduce sediment and fresh water to wetlands cut off by the levee system. In France, a similar structure could be built along the Rhône and should consider factors such as timing of sediment introductions as well as protection of human activities within the delta, including recreational, commercial and navigational activities. These questions will need to be answered to effectively manage structures such as these against future climate conditions.

Last year, a group of experts began to explore these questions, taking into account the needs of communities and ecosystems, and developed a set of recommendations for how best to operate a sediment diversion in the Mississippi River Delta. These recommendations are being addressed as part of the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) process for the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion.

For more information on sediment diversions and building land in the face of climate change, view our blog series answering 10 fundamental questions about the Mississippi River Delta and our series on key recommendations for diversion operations.