10 Years After The BP Oil Spill, This Barrier Island Is Slated For Restoration

To restore Louisiana’s coast, we need a suite of large-scale restoration projects across the coast working together to deliver maximum benefits to reduce land loss, restore ecosystems, and maintain healthy and diverse habitat. In our “Restoration Project Highlights” series, we take a deeper look at specific projects from our list of Priority Projects, highlighting why they’re needed and hearing local perspectives on importance.

*This blog was updated on 05/02/2022 to reflect current project status

Visible from the eastern tip of Grand Isle, Grand Terre is perhaps most well known as being the site of Fort Livingston at its western end, named after the former U.S. Senator of Louisiana and the 11th U.S. Secretary of State Edward Livingston.

Although this 19th Century fort was never completed, it was periodically occupied for different purposes from the Civil War through 1889. Eventually, the fort and the island was given to the State of Louisiana by the U.S. Government.

What is the West Grand Terre Barrier Island Beach Nourishment project?

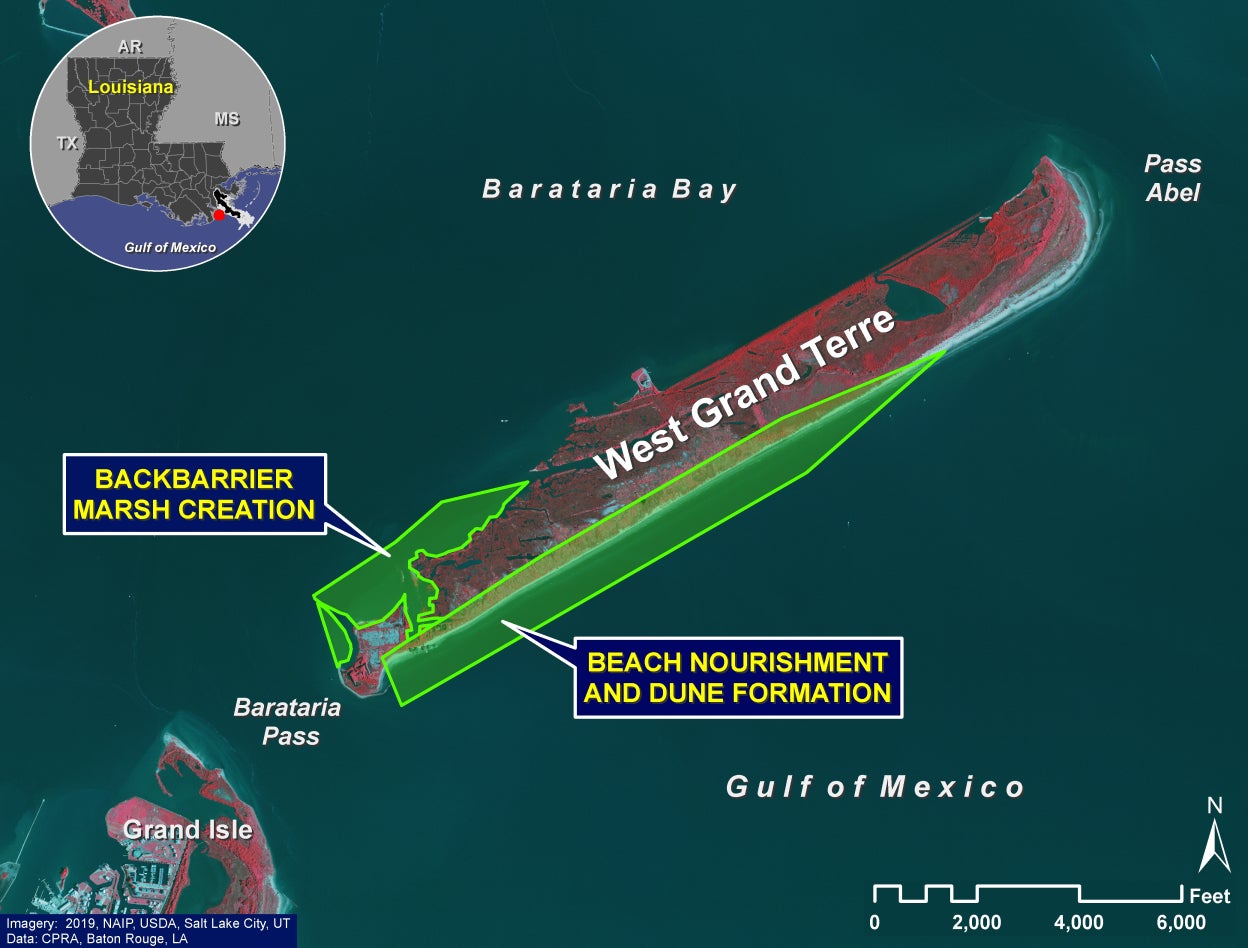

West Grand Terre is one of the Barataria Bay chain of barrier islands, stretching about 2.8 miles long. The shoreline eroded about 225 feet between 1996 and 2005, according to the Barrier Island Comprehensive Monitoring Program, which was about 50% faster than the previous 140 years. Furthermore, the entire front shoreline of the island was heavily oiled during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, putting its plants and wildlife at great risk.

West Grand Terre is one of the Barataria Bay chain of barrier islands, stretching about 2.8 miles long. The shoreline eroded about 225 feet between 1996 and 2005, according to the Barrier Island Comprehensive Monitoring Program, which was about 50% faster than the previous 140 years. Furthermore, the entire front shoreline of the island was heavily oiled during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, putting its plants and wildlife at great risk.

In the latest draft assessment by the Louisiana Trustee Implementation Group, released in December 2019, the West Grand Terre Beach Nourishment and Stabilization project was selected among three preferred restoration projects. This allowed the $65 million project to receive money provided by the BP oil spill settlement and take its first steps toward construction. This summer, work to remove dilapidated LDWF buildings on the west side of the island has been completed.

As the project moves forward, a 5,160-feet-long wall of rocks known as a revetment will be constructed around the west and northwestern end of the island, to stabilize it against the tidal forces along the 160-feet-deep Barataria Pass.

An estimated 2.5 million cubic yards of sediment will be dredged from a borrow site approximately 4.5 miles to the southeast to renourish the beach and dunes and expand the back barrier marsh. Like other renourishment projects, the final steps will be to add fencing and plant vegetation to reduce erosion.

The project is currently in active construction.

Why It’s Important to Restore West Grand Terre Barrier Island

Given the current rates of shoreline erosion, coupled with increasingly rapid sea level rise, and increased storm intensity, without restoration, without restoration action, West Grand Terre will eventually breach and succumb to the sea.

Of course, this region was also ground zero for the devastating impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, so it is fitting to see the completed restoration of these islands, which serve as the first line of defense for the extensive wetland estuary system to its north, protecting communities across southeastern Louisiana.

A Local Perspective

What Progress Has Been Made to Restore The Islands?

West Grand Terre is one of the last barrier islands in Barataria Bay to see substantial restoration since the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The other seven barrier islands that run east across the southern edge of Barataria Bay have collectively seen about $400 million invested in dune and back barrier marsh restoration, restoring approximately 4,000 acres of habitat using more than 44 million cubic yards of sediment, since 2007.

How Has Grande Terre Changed Over Time?

How Will This Project Benefit Wildlife?

Audubon, USGS, and Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program have each monitored bird populations following several beach renourishment projects, and all have documented substantial increases of colonial-nesting seabirds, especially Least Terns, Gull-billed Terns, and Black Skimmers. I have no doubt that West Grand Terre, in the 2022 nesting season following construction, will see the same.

The increased elevation will reduce the risk to nests from summer storm surges, and the wide-open sandy beaches will provide 360-degree views to watch for predators. Diamondback terrapins, listed as a “Near Threatened” species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, will similarly benefit from the increased habitat area and elevation.

The back-barrier marsh creation component will provide important mudflats and emergent marsh vegetation benefiting a variety of other birds, including Seaside Sparrows, Clapper Rails, Common Nighthawks, and Wilson’s Plovers.

Importantly, the project will also serve as a barrier to protect bay islands, including the newly restored Queen Bess Island that successfully hosted over 50,000 nesting birds in 2020, even though (and perhaps because) it was partially inundated by Tropical Storm Cristobal in early June.

Over the coming decades, as the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion rebuilds wetlands and reduces the tidal prism, there is hope that these barrier islands will experience lower erosion pressures from the daily tides. These rebuilt, larger and more sustainable islands will provide enhanced protections to other wetlands across Barataria Bay, supporting the diversity of wildlife and fisheries that depend on them.